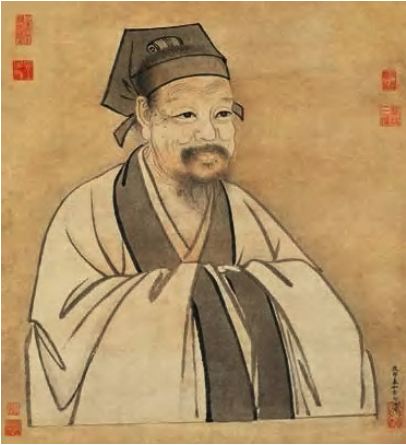

Surviving portrait

of Chu Weng Kung State Duke of Hui of the Song Dynasty by an unknown

artist, circa. 1330

ďState DukeĒ was the posthumous title

in Zhu Xiís honor and Hui was the prefecture where his ancestors had lived

for centuries. The area is now in Kiangsi

Province. Zhu Xiís father moved from there to

Fujian to serve as an official, and

Zhu Xi was born there.

Born in 1130 and dying in 1200, Zhu Xi

(also spelled as Chi Hsi) served many roles in ancient China as a

philosopher, classical commentator, scientific thinker and historian.

Born in Yuxi, Fujian Province, China

during the Song dynasty (1127-1279), Zhu Xi was a leader in the

rationalist wing of the neo-Confucian school developing in China from the

10th Century. His extensive commentaries on earlier Confucian thought,

published 1190 as the Si-Zi, established the Four Books (the Great

Learning, the Analects, the Book of Mencius, and the Doctrine of the Mean)

was the basic text in school education for almost 600 years. The civil

service examination system, for which his commentaries on the Confucian

Classics were officially declared as the orthodox interpretation in 1313,

prevailed until 1907. His conservative authoritarianism increasingly

dominated Chinese, Japanese, and Korean political, social, and cultural

perceptions until the 20th Century; the family rituals he formulated are

still the models of many Asian social customs.

While borrowing heavily from Buddhism,

Zhu Xi made use of the traditional philosophical vocabulary classical

Confucianism but augmented it with complex theoretical discussions of li

(the patterned regularity of existence) and qi (the psychosomatic stuff of

existence), giving precedence to the former.

This abstract distinction of 'li' and

'qi' had moral significance. They could be appealed to qualitatively in

explanations of both the goodness of humanity and how to realize it. In

his writings, he felt that the normative principle of human nature is pure

and good. Expressed in concrete form human nature is less than perfect,

but it can be refined through self-cultivation based on study of the

classics. Although Zhu Xi did not rule out introspection as a means to

illumination, he emphasized more on scholarly learning.

Zhu Xi also wrote on musical

notation, understood fossilization three centuries before Leonardo da

Vinci, realized that mountains had once been under the sea, saw the

Earth's origins in condensation from cosmic matter, and perceived the

universe as evolving and spinning from elemental force.

For a more complete write up on Zhu

Xi's work, visit:

http://www.humanistictexts.org/chuhsi.htm

|

1 |

|

|

12 |

|

|

23 |

|

|

|

Zhu

Xi |

|

|

Zhu Lan Yok |

|

|

Zhu Chu Yin |

|

2 |

|

|

13 |

|

|

24 |

|

|

|

Zhu Yeh

|

|

|

Zhu Yuan Ming |

|

|

Zhu Shi Da |

|

3 |

|

|

14 |

|

|

25 |

|

|

|

Zhu Quan |

|

|

Zhu Zhong Yan |

|

|

Zhu Gong Mao |

|

4 |

|

|

15 |

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

Zhu Xun |

|

|

Zhu Lak Hin |

|

|

Zhu Sheng Soi |

|

5 |

|

|

16 |

|

|

27 |

|

|

|

Zhu Lum |

|

|

Zhu Bik Chi |

|

|

Zhu Guo Cheng |

|

6 |

|

|

17 |

|

|

28 |

|

|

|

Zhu Bing |

|

|

Zhu Yin Bao |

|

|

Zhu Jong Soi |

|

7 |

|

|

18 |

|

|

29 |

|

|

|

Zhu Gi Yin |

|

|

Zhu Fong Weng |

|

|

Zhu Chong Guan |

|

8 |

|

|

19 |

|

|

30 |

|

|

|

Zhu Dao Zong |

|

|

Zhu Guan Lu |

|

|

Zhu Duc Koi |

|

9 |

|

|

20 |

|

|

31 |

|

|

|

Zhu Meng Lun |

|

|

Zhu Yuan Fa |

|

|

Zhu Jun Pak |

|

10 |

|

|

21 |

|

|

32 |

|

|

|

Zhu Yuan Yuan |

|

|

Zhu Yun Sheng |

|

|

Zhu Kim Ho |

|

11 |

|

|

22 |

|

|

33 |

|

|

|

Zhu Jian Kim |

|

|

Zhu Zhou Man |

|

|

Zhu Jing Xiong |

Garrett

Gee = #33 Zhu Jing Xiong

(Chu King Hung)

There

are many different ways of spelling Chu (Zhu, Gee, Chi, Chee)